In the years surrounding World War I a Japanese immigrant community flourished in the northern reaches of Manhattan—some thirty-five families—living near Broadway and Dyckman Street—operated businesses, planted victory gardens and registered for military service.

A physician, Dr. Minosuke Yamaguchi, who owned an art supply shop on Dyckman Street, led this Japanese colony.

His customers likely included fellow immigrants Toshi Shimizu and Hashime Murayama.

Shimizu, who lived at 38 Post Avenue, spent his early artistic career capturing familiar uptown scenes in works that included: Road to the Ferryboat, Impression of Dyckman Street, Summer Evening on Sherman Avenue and Hill Along the Hudson. He lived at 38 Post Avenue.

Shimizu returned to Japan before World War II where he achieved renown as a war propaganda painter.

Hashime Murayama, however, had no intention of leaving the States.

His ethereal renderings of a detailed and often microscopic world would soon enthrall a generation of National Geographic readers and revolutionize the field of cancer research.

Uptown Artist in Residence

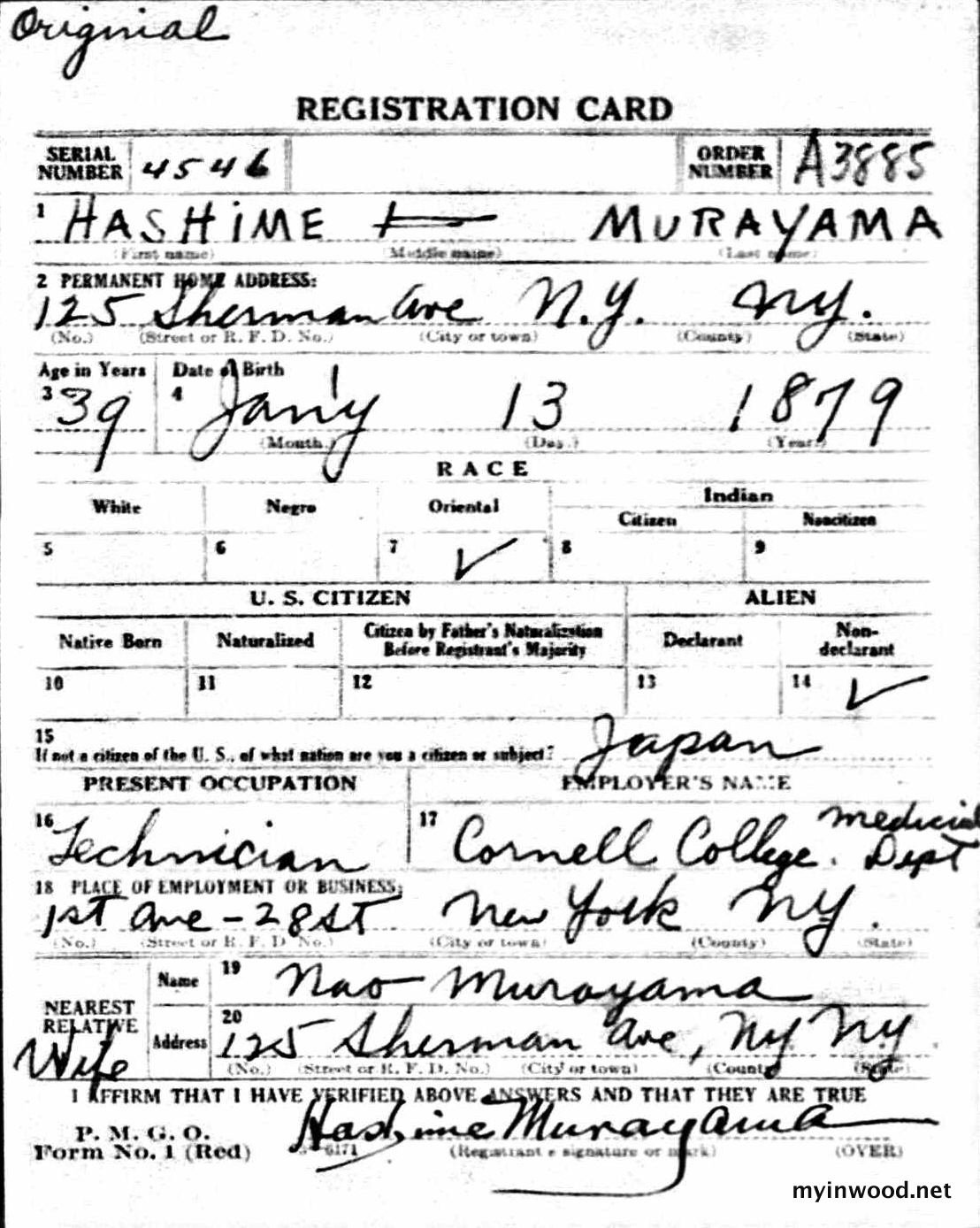

Hashime Murayama was born in Japan in 1879. He graduated from the Kyoto Imperial Art Industry College in 1905 and emigrated the following year.

In 1910 Nao Makino, the daughter of a former teacher, joined him in the States. The two married in New York City.

The couple eventually settled into a rented apartment located at 125 Sherman Avenue where they would raise two sons, Ken and Sutemi.

Neighbors in the five-story walk-up included immigrant families from Ireland, Hungary and Russia.

Murayama listed his occupation as “artist” when a 1920 census taker visited his uptown apartment.

National Geographic

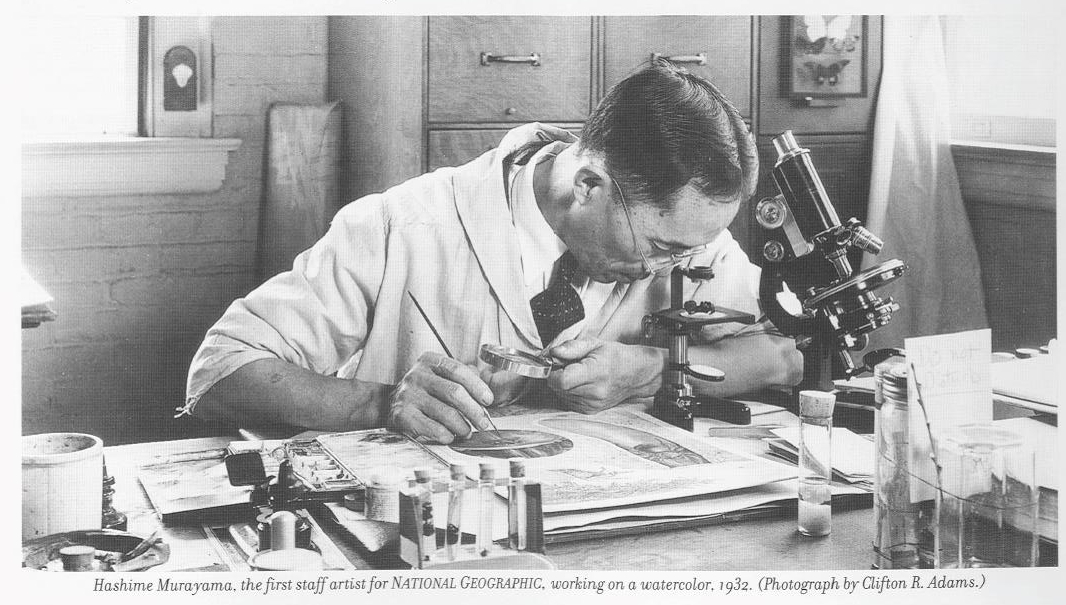

Initially Murayama found work as a technician at the Cornell Medical College. There he prepared slides and created illustrations of microscopic cells and organisms.

In 1921 he was hired by the National Geographic Society. Murayama would become the first staff artist employed by the publication.

For the next two decades his stylized depictions of fish, birds and insects were regular features of the magazine.

According to a Society biography Murayama “joined the staff of National Geographic at a time before reproducing color photography was common. Dedicated to pictorial precision, he was known to have counted the scales of a fish to ensure the accuracy of his paintings.”

His works for the publication were colorful and otherworldly.

In the early 1920’s the family moved to Washington, DC where he continued illustrating for the Society.

A World at War

In 1941 Murayama was dismissed by National Geographic because of his immigrant status.

After Pearl Harbor Murayama and his wife were required to register as illegal aliens.

Cornell, his early employer, took him back in.

A 1949 directory listed his address as 690 Fort Washington Avenue—a twenty-minute walk from his old Sherman Avenue apartment.

Back at Cornell Murayama collaborated with former colleague Georgios Papanikolaou in revolutionary work involving the early detection of uterine cancer.

Two arrests, in 1942 and 1943, followed—but his skilled hand saved him from detention.

The Alien Enemy Hearing Board recommended that the couple be placed in an internment camp, but the Attorney General overruled—citing Murayama’s “microscopic sketches in colors of uterine cancer cells” at Cornell. “It is said,” the investigator concluded, “that he is the only person in the United States who can do that kind of work”.

He would remain under close surveillance until the end of the war.

Postscript

Through 1954 Murayama continued his meticulous illustrations of uterine cancer cells.

The research team succeeded in developing a test for detecting uterine cancer—the “Pap” smear.

Hashime Murayama died in 1954.

In 1966 his widow, Nao Murayama, became an American citizen.