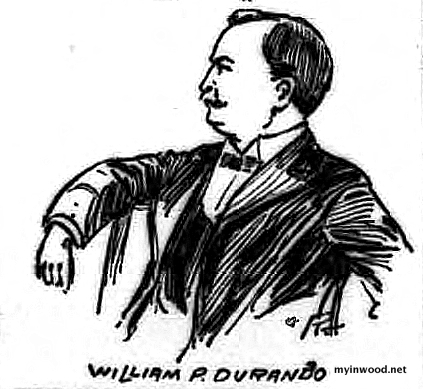

Billy Durando was a celebrated personality in turn-of-the-century New York.

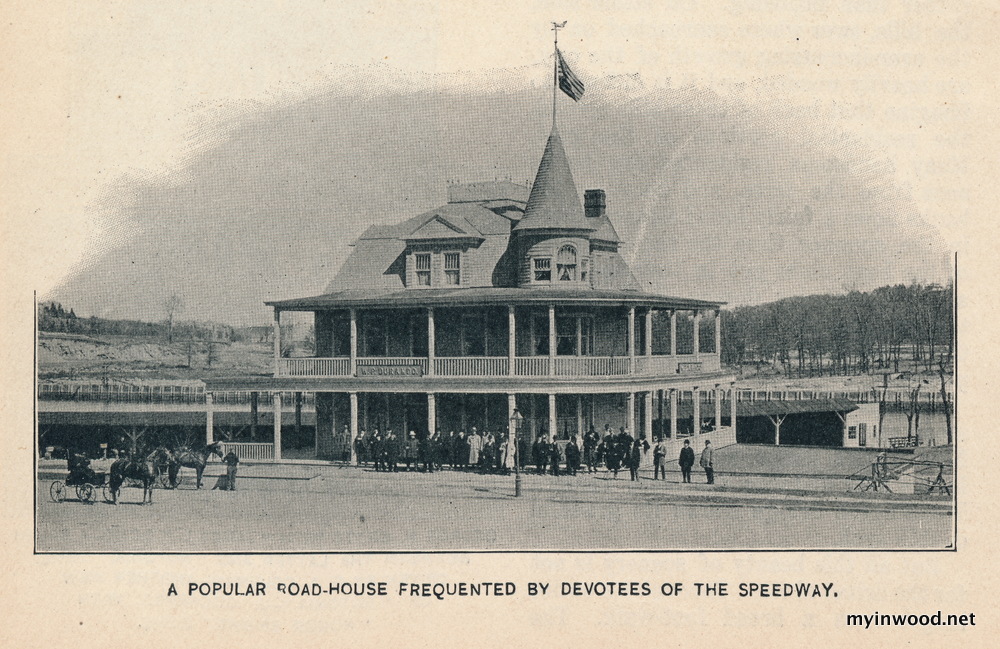

The silver haired impresario owned a string of roadhouses along Manhattan’s Harlem River Speedway.

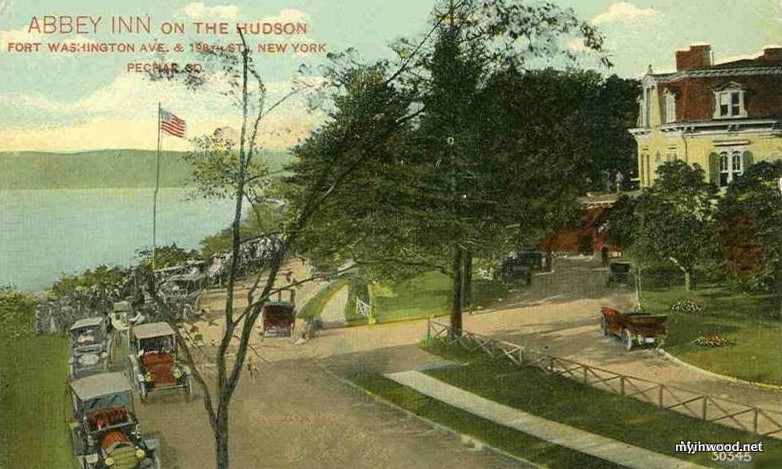

The Abbey Inn, The Standard, the notorious Speedway Inn and Durando’s Hotel, simply known as The Club—they were all his.

Inside Durando’s Dyckman Street Club patrons drank, feasted and debated horseracing late into the night.

Bold-faced names the likes of Nathan Strauss and Jay Gould once vied for his attention.

Not a bad for a former butcher’s assistant.

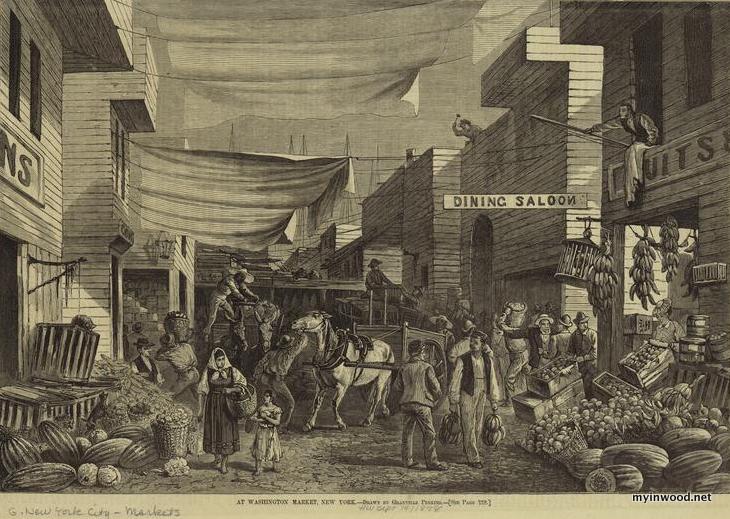

Beauty of the Washington Market

William P. Durando was born in 1847. He was one of six children. His father, Stephen, a tailor, operated a clothing stall on Fulton Street. Both his father and mother, Catherine, were native New Yorkers. The family lived in Manhattan’s Thirteenth Ward. The Lower East Side neighborhood was then home to a staggering number of German immigrants who poured into the city during the 1850’s.

He wore a full mustache framed by pink cheeks. Folks described him a suave.

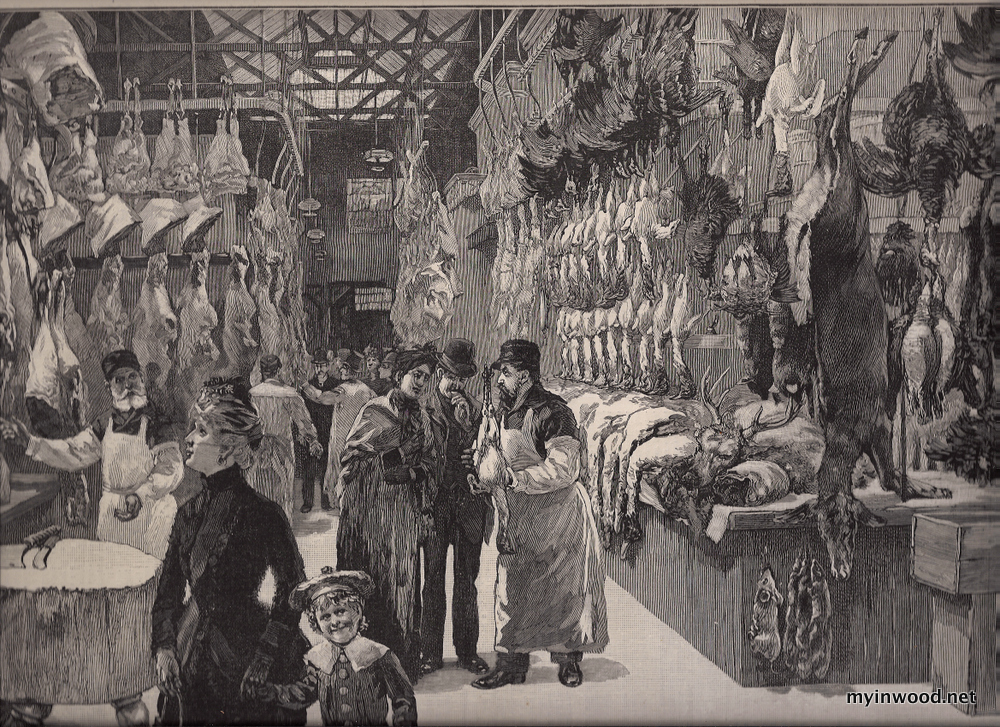

As a young man Durando found work as a butcher’s assistant in the nearby Washington Market.

Today the site of the World Trade Center complex, the market was a popular destination in the 1800’s. Merchants tended to countless stalls and pushcarts, spread over some dozen blocks. There, in the open air, they hawked a pungent array of meats, vegetables, fruits and seafood.

Along muddy pathways all manner of consumer shopped for jerked beef, blood pudding, quail, turtle steaks, oysters, truffles and pokeweed.

For nearly thirty years William P. “Billy” Durando butchered all variety of animal.

Vendors inside sprawling market saw Durando as their unofficial Mayor. He was respected, well liked and known for settling disputes.

By the 1880’s he had two full-time assistants in his employment.

From stalls 14 and 15, along Vesey Street, Durando supplied beef, veal, mutton and lamb to “steamboats, hotels, and restaurants, as well as families, at the lowest market rates.” (Market Assistant)

“This establishment,” read an 1888 description, “deservedly maintains a high reputation for choice quality and excellence for all food products handled. It is one of the neatest and best-kept establishments in the market.” (Illustrated New York, 1888)

Over the course three decades Durando’s reputation and oversized personality earned the butcher a certain celebrity status—he was variously known as the “Beauty of Washington Market” and the “Daisy.”

His fame would soon extend beyond the Market.

The Biscuit Man’s Wife

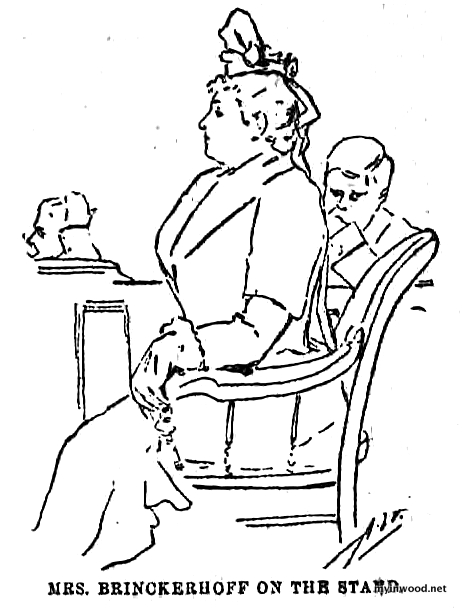

Durando made headlines in the late-1880’s after an affair with Henrietta Brinckerhoff, the wife of wealthy biscuit manufacturer Daniel. D. Brinckerhoff, became public.

A brutal divorce trial dragged on for years. The scandal sheets gave daily updates from the courtroom.

Durando and his mistress seemed unconcerned. Even amused.

Henrietta shot Durando a “ghost of a smile” as key witness, Samuel Fuel, an elevator attendant, testified that the butcher and the biscuit man’s wife had rendezvoused secretly at St. Cloud Hotel on Broadway and Forty-Second Street for a number of years.

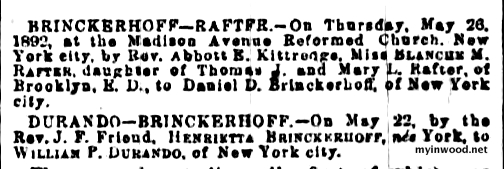

Durando apologized for nothing and married “Ettie” a month after her divorce was made legal in 1892.

The butcher’s new wife was fourteen years his junior—and she was a knockout. Blond hair. Mischievous eyes. Tailored dresses. Seal skin capes. Heads turned wherever she went.

The biscuit man moved on as well—marrying his fourth wife just days after divorcing his ex. The irony of publishing dueling wedding announcements in the same edition was not lost on editors.

Through it all Durando seemed to enjoy the publicity. How often did market boys marry society ladies?

Durando could have stopped there—he lived an enviable existence.

But the Washington Market butcher wanted more. He yearned for the adulation reserved for the club owners and high-end restaurateurs he supplied from his noisy and blood-soaked patch of lower Manhattan.

And so it was that the “Daisy” reinvented himself—completely.

The Harlem River Speedway

In July of 1898 New York’s famed Harlem River Speedway opened on Manhattan’s east side.

The three-mile equestrian raceway ran beside the Harlem River from 155th Street to Dyckman Street. Here Manhattan’s upper crust raced prized steeds on an exquisitely groomed track—today the site of the Harlem River Drive.

The project had been controversial from the start.

The roadway was built with the pleasure of the wealthy in mind, but many were incensed to learn the five million dollar project had been taxpayer funded.

The general public reaped no benefit from the expense. The site was off-limits to pedestrians, coaches and bicycles.

These concerns did not bother Durando.

From his stalls on Vesey Street Durando listened with fascination as patrons told him of the wealthy masses gathering on the bank of the Harlem River.

Durando sensed an opportunity. His mind raced with visions of roadhouses, gambling, feasting and free flowing libations.

Soon all of New York would know the name Billy Durando.

His first venture, The Standard Roadhouse, overlooked the Speedway on 154th Street.

The Standard Roadhouse

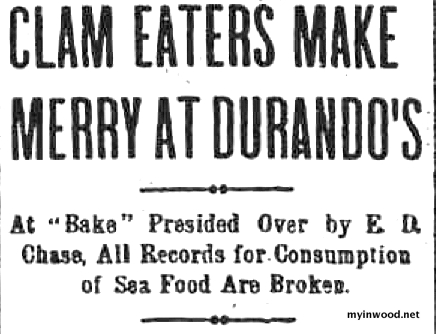

In October of 1898 hundreds of familiar faces from New York society gathered at Durando’s new Standard Roadhouse for what would become an annual clambake.

Durando’s bacchanalias would become legendary social events.

“It required ten barrels of clams, four barrels of oysters, 300 lobsters, 150 pounds of striped bass, 100 pounds of tripe, 300 spring chickens, several barrels of sweet potatoes and spuds and an entire cornfield was denuded to furnish the young roasting ears to feed the hardy appetites of the reinsmen and their wives and sweethearts,” read one description. (Morning Telegraph, October 6, 1898)

“The dining rooms and verandas were filled,” the account continued, “and it kept almost a regiment of waiters busy running from the house to the open space where the viands were steaming to supply the table. There was feast of bake and flow of champagne and other liquids properly mixed with reason. Music and laughter filled the balmy air.”

Durando’s liquor-soaked party was just getting started.

“A little donkey was raffled for after the feast,” reported the Telegraph. “Capt. Jack Davis won, and amid streaks of laughter, rode the beast around the piazza, through the barroom, into the large dining room, where the orchestra was planted, and there proceeded to execute a wing dance with the burro as his partner, but the wise looking little fellow could do nothing swifter than a minuet and Capt. Jake had him led away.”

Durando’s dream, hatched in a downtown market, was now a reality. The former butcher now counted among his patrons a long list of rich and powerful New Yorkers, which included Jay Gould, Nathan Strauss, John B. McDonald and Harry Payne Whitney.

Within years Durando would open other successful roadhouses including the Abbey Hotel on 154th Street and Fort Washington Avenue and the Speedway Inn on 192nd Street.

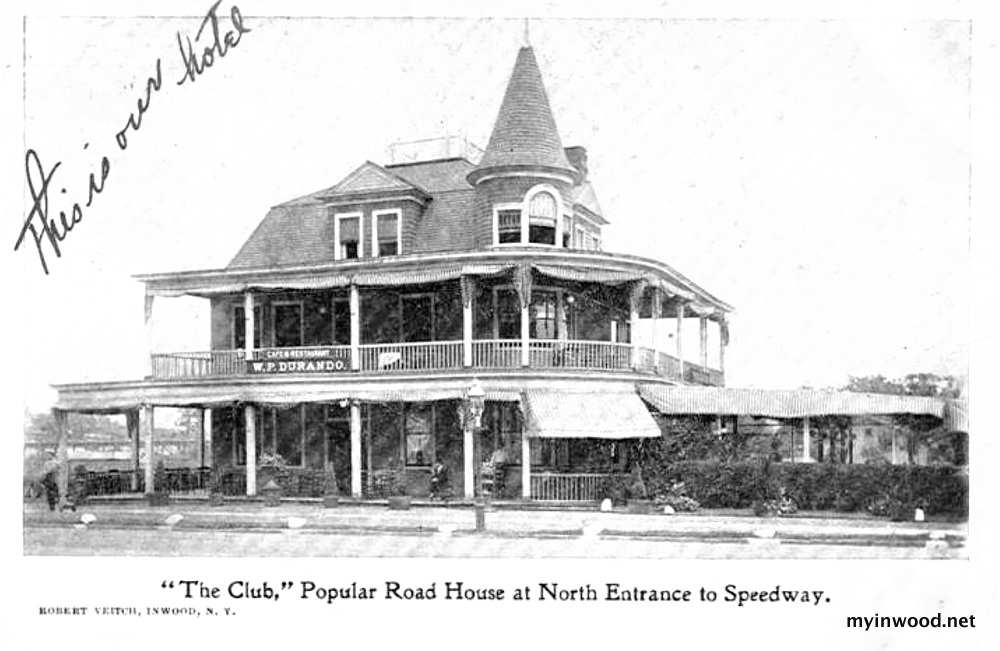

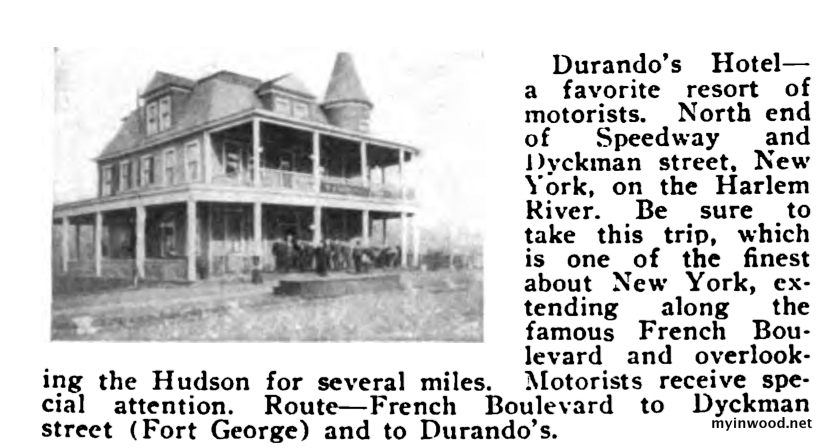

Perhaps his best-known venture was located at the northern end of the Speedway on Dyckman Street.

The Club

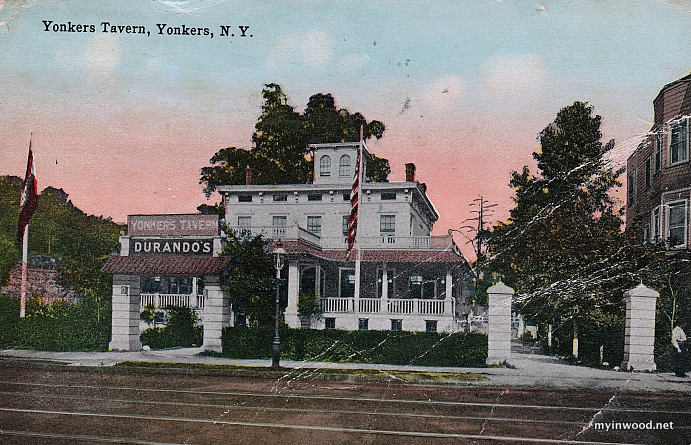

“Durando’s Hotel,” known to most as the “The Club,” was a concession Durando leased from the Park’s Department. The new roadhouse was a quick favorite with horseman when it opened in 1902.

The roadhouse was nothing more than an ancient former residence with a broad wrap –around porch. The two-story wood-frame home was painted yellow on Park Department orders.

“The new hostelry is most happily located,” wrote one newspaper. “It is situated right at the riverbank and boats can land at the wharf, carrying passengers from the Central Bridge, thus making it easily reached by those who do not choose to drive.”

“From the porches on the roadside,” the description continued, “spectators will be enabled to witness all the brushing, and from the riverside a good view of the boat races may be had.” (Morning Telegraph, July 12, 1899)

Here again Durando repeated his time-tested formula. Liquor flowed freely and the intoxicating smells of piles of seafood, roast beef and chicken permeated the night air.

In 1902 a reporter for the New York Evening Telegraph described the fragrant scene.

“Smoking heaps of blankets” spread out in front of the Club alerted passerby that a clambake was in the works, wrote the Telegraph.

“Even the cops lined up to get a whiff of the pungent and satisfying odor of baking clams,” the account continued. “A curious chauffer, attracted by the fragrance of the bake, tried to run his automobile down the Speedway to the club house, but was promptly stopped by rapid bluecoats.” (New York Evening Telegraph, September 24, 1902)

“While the sunset glow still lingered over the river,” wrote the Telegraph scribe, “and even until the moon had risen and cast its silvery gleam on the broad veranda of the club house, the bake continued. Twenty-five bushels of clams, 200 pounds of chicken, 200 ears of corn, 150 fishes, two bushels of potatoes and watermelons sufficiently constituted the store of edibles consumed.”

Durando felt completely at home standing on the porch of the old yellow roadhouse on Dyckman Street.

There, as the years passed, he also fell in love with horseracing. Never happy on the sidelines, Durando purchased a collection of world champion trotters. Many he raced himself. His favorite, a horse named Malachi, was later sold to Nathan Strauss.

For more than a decade life was grand.

Then came the automobile.

End of an Era

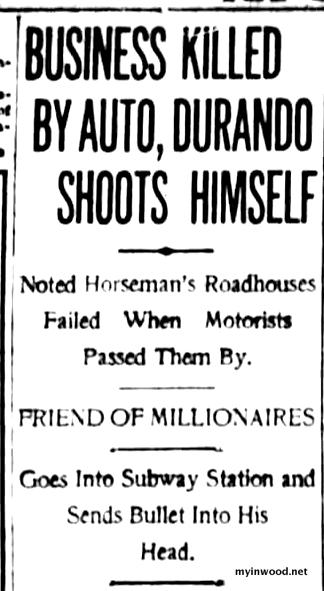

The Speedway and Durando’s roadhouses quickly succumbed to the popularity of the automobile.

Riding parties could now venture far outside city limits. The picturesque Speedway quickly fell out of favor. Its days were numbered.

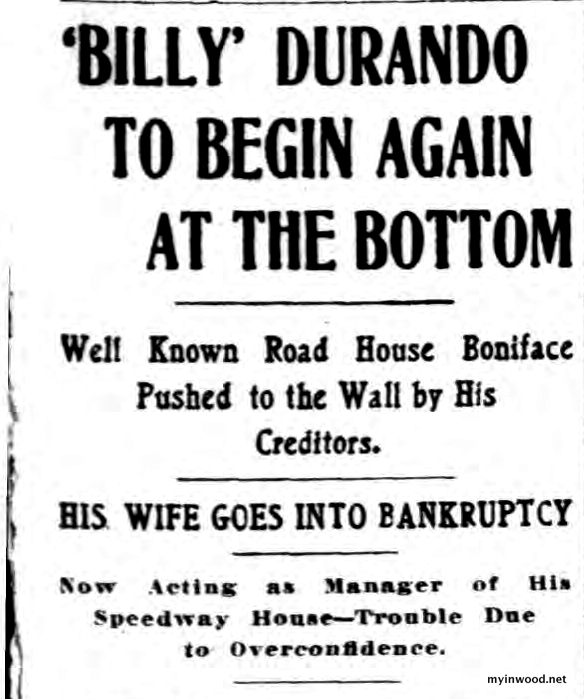

One by one Durando’s roadhouses failed. Collateral damage.

The acclaimed impresario sank to once unthinkable lows to stay afloat.

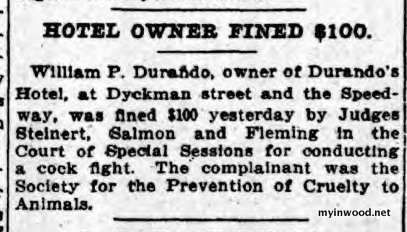

In 1912 police raided the Club.

Durando had been hosting cockfights in the same rooms where he once entertained Vanderbilts. Police arrested forty-three men and confiscated thirty-six game cocks whose fighting names included Blinker, One-Eyed Colleen, Irish Gray and Waldo. Durando could only grin when, at trial, a rooster marked “Exhibit A” escaped from its coop inside the crowded courtroom. He was fined $100 for running a cockfight.

“Talk about your automobiles,” a wistful Durando told reporter just months after his arrest, “but give me a pair of long tailed horses for beauty.” (New York Tribune, June 16, 1912).

By years’ end his beloved Club was shuttered.

A subsequent venture catering to automobile excursionists, The Yonkers Tavern, closed in April of 1915. The once far-flung locale proved too close to city limits to hold interest.

Despite his best efforts Durando was bankrupt— the dream was over.

For much of his life the now silver-haired merchant was known for his generosity.

“In the days of his affluence,” said one reporter, “he was known as ‘easy money’ and it was said he never refused to lend or give to anyone he knew.” (The Evening World, May 26, 1915)

Now, with the creditors circling, the former Beauty of the Washington Market found he had no one to turn to.

Many of his wealthy former patrons were dead. Those who owed him money refused to take his calls.

He would gladly run an elevator if only someone would hire him, he told one friend.

If only he could reinvent himself once again, but at sixty-seven, who would have him?

One Last Taste of Brandy

On May 25, 1915 Durando patted Ettie on the cheek, kissed her goodbye and said, “Now I’ve lost everything in the world, now my life is over.” (The Evening World, May 26, 1915)

These would be his last words to his spouse of twenty-five years.

Witnesses reported that Durando entered a saloon sometime after his departure from his home inside the Continental Apartments located at 4180 Broadway near West 176th Street.

“I wish you would give me a small bottle of brandy,” he told the barkeep. “I’m not well physically and my heart is heavy.”

“I just went to a moving picture show hoping it would cheer me up,” Durando continued. “It didn’t. Maybe this brandy will.” (Evening News, July 2, 1915)

Around six o’clock Durando was seen “pacing excitedly” on the uptown platform of the 181st Street subway station.

According to witnesses “he let several trains pass making no effort to board them. Between trains he would sit and as one approached he would begin to walk again.” (Evening News, July 2, 1915)

Nearly an hour later, around seven o’clock, as a northbound train approached, Durando put a large-caliber pistol to his to his right temple and pulled the trigger.

A crush of rush hour commuters spilled off the train to view the horrifying scene.

“Why, that’s Billy Durando,” a woman recognizing the snow white hair and long mustache exclaimed.

Someone who knew Durando walked quickly to his home to inform his wife.

“Now I’ve lost everything in the world,” was all she could say.

Police found six letters in his pocket. On hotel stationary Durando had written to friends and relatives describing his plan to commit suicide. Durando had affixed postage stamps to all of the letters. Except for Ettie’s. He must have known that hers would be hand delivered.

Durando’s death was front-page news the following morning.

In 1919 the Harlem River Speedway was opened to automobile traffic. The roadbed was paved in 1922.