On a summer evening in 1935 some fifteen thousand boxing fans gathered under the floodlights of the Dyckman Oval to witness Puerto Rican Sixto Escobar and Coney Island kid Lou Salica battle for the world bantamweight championship title. The two fighters, at the peak of their careers, each weighed 117-½ pounds—one half pound less than the 118-pound bantamweight limit.

The fifteen-round bout was described by one sportswriter as one “of the most savagely fought battles ever staged by little men in the New York area.” (Pittsburgh Post Gazette August 27, 1935)

The judge’s verdict, amid hisses and boos, would become one of the most contested decisions in the history of the Oval.

El Gallito

Sixto Escobar, nicknamed “El Gallito” (The Rooster), was born in Barceloneta, on the northern coast of Puerto Rico, in 1913. Escobar was seventeen when he fought his first professional bout in 1931—defeating Luis “Kid Dominican” Pérez with a knockout.

The teenager would spend the early part of his fighting career in Venezuela due to a lack of talented opponents at home. After honing his skills in Caracas he moved to New York.

On August 8, 1935 he met Pete Sanstol in a twelve round National Boxing Association World Bantamweight Championship fight in Montreal.

The epic battle secured Sixto’s place in boxing history.

“The two dressing rooms, after the fight, told the story,” wrote Elmer Ferguson of the savage battle in Montreal. “On the east end of the Forum, Escobar sat on the edge of the table, unmarked, his legs swinging, a broad grin on his face. ‘He tough,’ was his laconic tribute to his beaten Norse foeman. Sixto didn’t have any souvenirs of the fight. He came out without a scratch, without even a swollen hand despite the crashing attack he rained on Sanstol’s face and head. Across the big Forum, on the west side, it was different. A swollen, flattened nose, puffed and swollen lips—these were all that was visible of a figure that lay prone on the table, covered with blankets and towels. Cubes of ice were being passed across the fevered lips to fight off further swelling. That was Sanstol, after his gallant stand.”

The 1935 fight was the first boxing World Championship ever won by a Puerto Rican. When he returned to Puerto Rico after the fight the Governor ordered that all government buildings be closed so that employees could attend a parade held to welcome home their native son.

Lou Salica

Lou Salica was born a contractor’s son in Brooklyn in 1912. He was one of fourteen children and had a sixth grade education.

In the late 1920’s he won dozens of fights on the amateur circuit before going professional in 1932. That year Salica won a bronze medal in the flyweight division in the summer Olympics.

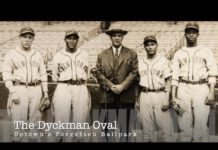

The Venue

When the Dyckman Oval first appeared in the sports pages in January of 1920 it was a modest affair located at 204th Street and Nagle Avenue. That first year the Oval was used primarily for ice skating competitions.

Soon boxing was added to the roster. Pugilism would become a staple of the Oval for the decades that followed.

By 1929 years of lawsuits and mismanagement had left the once thriving facility on life support.

It was not until 1935 that investor Alejandro Pompez turned the green cathedral of upper Manhattan around. A Harlem numbers broker, Pompez gave the ailing Dyckman Oval a sixty thousand dollar shot in the arm to showcase for his prized baseball team, The New York Cubans. Under his renovations the Dyckman Oval was transformed into a shining new arena with modern conveniences like floodlights for playing well into the night.

A master showman, Pompez knew how to fill the house. If Babe Ruth didn’t dazzle them then perhaps a boxing exhibition with Joe Louis, a new car raffle—whatever it took. That summer evening organizers draped a ring over home plate so the two bantamweights could slug it before a sell-out crowd.

The Fight

Escobar and Salica battled over the course of fifteen grueling rounds. Arriving at the wooden stadium most in attendance rooted for Salica. He was after all the hometown fighter.

The first round, by all accounts, was dead even. By the second round Sixto’s technical superiority became evident.

Escobar “is a good boxer, schooled in most tricks of the ring,” wrote Ed Hughes in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. “He was much more the rapid hitter, mixing up his jabbing with whizzing right shots that must have made Lou’s teeth rattle. The Puerto Rican was especially effective in close. Here he seemed to smother Salica’s best efforts, the while dealing considerable damage himself. He had the knack of keeping his arms disentangled, shifting position to shoot uppercuts or rake Salica’s ribs with his short hooks. Round after round Salica made the mistake of trying to box with his slippery foe. The Coney Island youth is a nimble performer himself, but in deft glove play he was several notches below his opponent. He couldn’t keep his face out of the Escobar jabs and although he nailed the brown-skinned boy with some hard shots to the chin, the wallops didn’t seem to slow up Sixto.”

The seasoned sportswriter estimated that Escobar outpunched his Coney Island opponent three or four to one in their many exchanges.

“The Salica corner pleaded with its gladiator to cut out the boxing and ‘go hit him,’” wrote Hughes. “In the eighth round the Coney Island scrapper did this. He went after the pestiferous little Puerto Rican with a sort of desperate ambition, forcing Escobar back with the sheer fury of the attack. Salica looked good in this session. He shot a stinging right over Sixto’s guard that took effect on the jaw.”

Sixto quickly regained control of the fight “and he out walloped his rival in several other spiteful exchanges. Although Salica tried hard enough he never did look as good in any succeeding round. Escobar steadied himself. He boxed neatly, made Salica pay for his misses with sharply driven punches to the head or body and generally held an upper hand.”

Midway through the fight Salica’s manager, Hymie Caplan, seemed to sense the young Puerto Rican’s technical superiority. Caplan urged his boxer to “get natural.” Caplan, who favored cigars and fedoras, couldn’t believe the punishment doled out by Escobar. This kid “musta had a lot of fights” he muttered from Salica’s corner. “Relax,” he shouted to Salica.

Late in the fight Salica did “get natural.”

“He slugged with no little abandon in the 13th,” wrote the Brooklyn Eagle sportswriter. “And he went all out in the final round, which I thought he won.”

By the end of the fifteenth round it was clear to nearly everyone in the Dyckman Oval that Sixto Escobar was the champion.

“Escobar, in my mind, was clearly the master, winning almost every round,” Hughes concluded. “My count gave the Puerto Rican 12 out of the 15, the first being even and only the eighth and the fifteenth being awarded to Salica. Several rounds were close and might have been given either way, but it seemed to me Sixto was the superior party, even in the doubtful ones.”

But the world bantamweight belt did not go to Escobar.

Leaning over the ropes referee Artie Donovan told boxing commissioner Bill Brown that he and the other two judges had decided to give the decision to Salica. He explained that while Escobar landed many more blows they felt that Salica had “hit harder” than his opponent.

Sixto looked bewildered as Salica stood center ring holding the world championship belt above his head. The Oval thundered with boos that drowned out the cheers for the newly belted Salica.

Sportswriter Hughes was bewildered as well.

“How the officials doped it out that Salica won a majority of the rounds or inflicted the heavier punishment is too much for me,” Hughes pondered. “Perhaps there have been some changes in the rules that have escaped me. It must be that a boxer is penalized the round for unloading left jabs in the other fellow’s face and belting him about the body. If so, I could understand Salica’s winning. Sixto was mighty liberal with both of these types of punishment.”

“There were tears in Escobar’s eyes as he protested the decision,” wrote the New York Post.

“I think I win fight,” Escobar told reporters in broken English. “I win eight rounds. He no hurt with punches. I want to fight him again.”

The Post reporter caught up with Salica at his father’s Coney Island restaurant later that evening. The boxer, his face puffy from the fight, was enjoying a spaghetti dinner with his thirteen siblings.

“Sure he can have a return fight,” Salica stated between bites of pasta. “Any time he wants it,” added manager Hymie Caplan.

Rematch

Less than three months later the two foes met again at Madison Square Garden.

Escobar again dominated the fifteen round fight. For good measure, Sixto dropped his rival to the floor for a nine count in the third round.

The 22-year-old Puerto Rican won the rematch by unanimous decision.

No longer the victim of a hometown verdict, Sixto finally received his well-deserved laurels.

Estadio Sixto Escobar (Sixto Escobar Stadium) was dedicated in San Juan, Puerto Rico the following year.

Postscript

Sixto would lose his championship belt to Harry Jeffra in September of 1937. Undeterred, “El Gallito” would continue to fight before sell-out crowds until he was drafted into military service in World War II. In sixty-four fights he was never knocked down.

Unable to meet the weight restrictions after his discharge, Escobar returned to Puerto Rico where he became a liquor spokesman and salesperson. After his death in 1979 at the age of sixty-six Barceloneta erected a statue to honor their hometown hero.

In 2002 Escobar was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

In 1944 Lou Salica was arrested on conspiracy charges for his alleged role in a salary kickback racket that was enforced with threats and beatings. He later worked at the Fulton Street fish market. He died on Jan. 30, 2002, at the age of 89.