Few institutions can claim a direct connection to founding father Alexander Hamilton, but such is the case with Manhattan’s northernmost branch of the New York Public Library—the Inwood branch—initially a circulating collection kept afloat by a endowment from Hamilton’s widow, Eliza.

But for a School

In the early 1800’s the northern end of Manhattan was sparsely populated.

Education was nearly inaccessible to the children of many of the region’s European settlers—a mix of landowners, farmers, laborers and tavern-keepers.

Inside this northern expanse, which included Washington Heights and Inwood, there was not a single school north of 155th Street.

The situation was desperate, but a powerful benefactor would provide what the City had long denied uptown citizens—a proper schoolhouse.

The Hamilton Free School

In 1818 Eliza Hamilton, the sixty-one year old widow of American founding father Alexander Hamilton, opened the first school in Washington Heights.

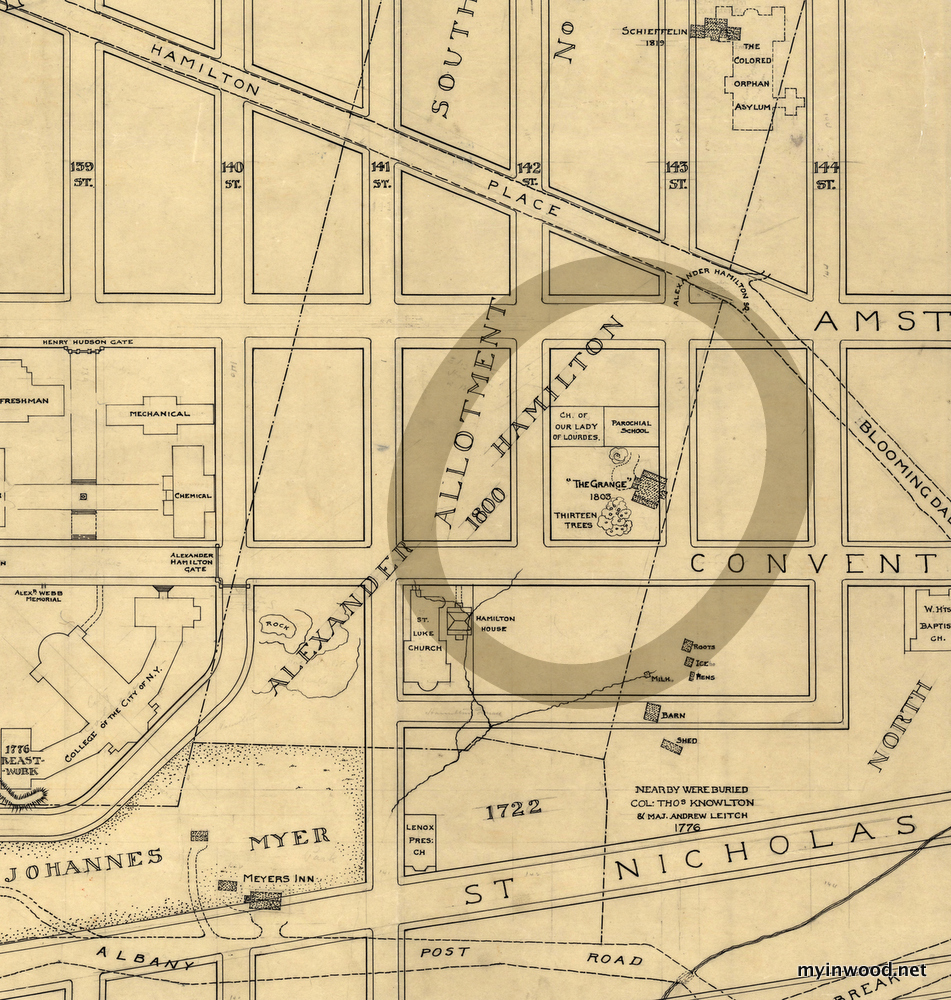

The widow Hamilton, whose husband had been killed in a duel with Aaron Burr in 1804, was familiar with the region. The couple’s estate, The Grange, named after Hamilton’s ancestral home in Scotland, stood near the current intersection of West 143rd Street and Convent Avenue.

The Hamilton Free School, as it was called, charged no tuition—Eliza believing that all children, even poor children, should be educated; if for no other reason than to possess the ability to read the Bible.

Eliza’s schoolhouse sat on a knoll near the current intersection of West 187th Street and Broadway.

In 1923 former student William Herbert Flitner, born in 1842, wrote “the school was a small affair, where elementary subjects were taught by one teacher, who was also janitor of the school.”

Flitner grew up in a wood frame house on Bolton Road, just off Dyckman Street, inside what is now Inwood Hill Park. He was one of five children. His father, William Ladd Flitner, had was a ship captain.

“The school numbered about forty scholars,” Flitner recalled, “really a primary school—boys and girls; one teacher for all; and all the scholars came from the locality between High Bridge and Kingsbridge. The public school provided by the city was at 155th Street, too far away for many of us.”

Alumni, Flitner remembered, included children of the Dyckman, Ryer, Bowers, Cheesbrough and Oblinns households and “others of the older families.”

And so it went until the 1850’s when the schoolhouse was destroyed in a fire.

An Uptown Library

Uptown city services improved considerably in the decades after Eliza Hamilton constructed the much-needed schoolhouse. (Eliza died in 1854 at the age of 97).

Upon learning that a new public school was being constructed on 183rd Street the trustees decided against rebuilding the Hamilton Free School.

Instead the land was sold—the proceeds to be used to establish another “first” for the region.

Perhaps a school was no longer needed. But a library… The region could certainly benefit from a library.

Soon after the fire the trustees of the Hamilton Free School partnered with the descendants of an old of Dutch landowning family whose holdings included a great deal of real estate just north of Washington Heights.

The Dyckman family was well-known in northern Manhattan. Their properties stretched through the Inwood valley and beyond. Patriarch Jan Dyckman had arrived in New Amsterdam in the 1600’s. Jan’s descendants already maintained a “Socratic Library” in the region—then known as Tubby Hook.

A Colonial Dutch farm house, now a museum, and a major thoroughfare, Dyckman Street, today bear the family name.

The two parties shared a common interest—the construction of a library.

Their relationship was quickly formalized.

The Dyckman Connection

In 1860 the Dyckman Library was incorporated “to receive from the trustees of the Hamilton Free School the sum of $1,000 and with this, or any other funds, to establish a library near Tubby Hook.” (Chapter 330 of the laws of that year)

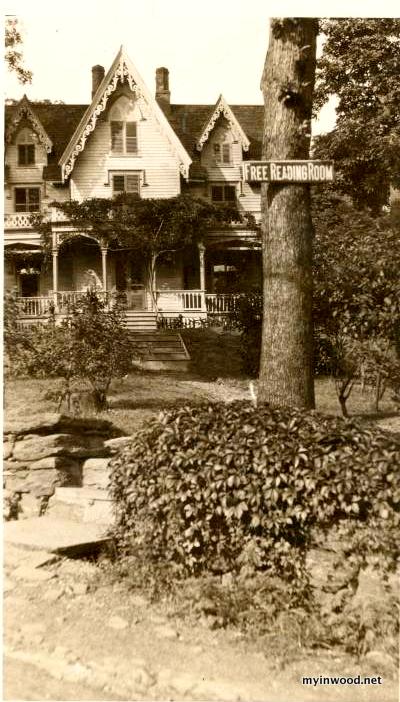

Thus, a portion of the Hamilton funds were “transferred” to the trustees of the Dyckman Free Library—to secure a permanent home for the wandering collection of books housed primarily in the old Flitner home on Bolton Road.

Isaac M. Dyckman, an original Dyckman Library trustee, brokered the sale of several lots and a house near Broadway and West 204th Street owned by a lumber merchant named Alfred Walton.

“They were in this purchase materially assisted by Mr. Dyckman, one of the trustees named in the act of incorporation of the Dyckman Library, who contributed the balance needed for the investment over and above the Hamilton School fund then in the hands of the trustees,” recalled former student William Flitner, later a trustee of the fund.

Dyckman must have been pleased with the arrangement.

He described the library as a “connecting link” between the community and Eliza Hamilton, for whom he had fond memories that extended far back to his own childhood.

“I was acquainted with the Widow Hamilton; she always went by that name,” Dyckman recalled, “and saw her often when I was a boy. I was wonderfully impressed with her dignity and appearance.”

But Eliza’s “connecting link” would be put on hold.

The city seized the new location in condemnation proceedings. The neighborhood was growing and private property was often appropriated to make room for roads and other city services.

The old Walton residence, meant to house the collection, was razed.

The ever-growing collection of books again lacked a permanent home.

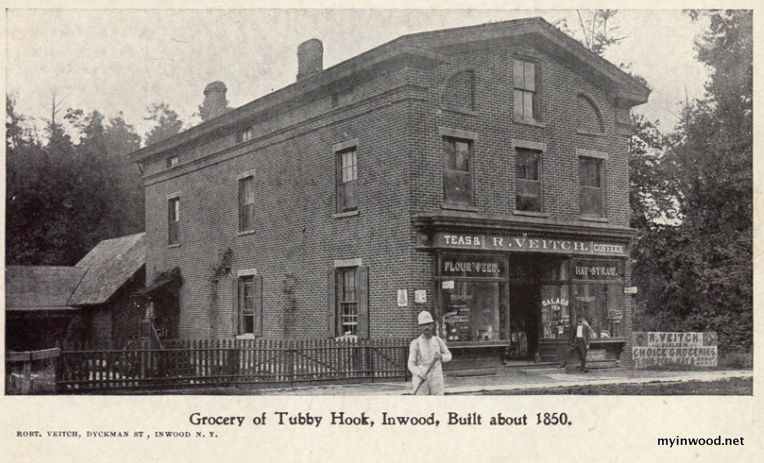

Veitch’s General Store

In 1902, when the New York Public Library “began providing services to the Inwood neighborhood in collaboration with the Dyckman Library, ” alternate space was needed to house the incoming volumes. (NYPL website)

The trustees of the Dyckman Library called upon Dyckman Street shopkeeper Charles Veitch, whose family owned the region’s only dry goods store, to manage much of the collection.

Veitch “loaned them out from the Inwood store and kept track of them,” Flitner recalled, “for which he was paid a small compensation out of the funds of the Dyckman Library.”

“This arrangement,” Flitner wrote, “ lasted for some time and was the nucleus of the present arrangement by which a reading room and library has been founded in our house at Inwood and in which both the books of the New York Public Library and the Dyckman Library are loaned to the people in the neighborhood for use.”

The system wasn’t perfect, but served the needs of the then rural area.

Then the subway arrived.

A Committee of One

When the first trains rolled out of the tunnel and into the Dyckman Street station in 1906, new apartment buildings stood ready to greet the arriving passengers.

Seemingly overnight the Dyckman region had gone from country to city. The population swelled. The antiquated lending system, cobbled together over so many decades, was overwhelmed.

Like Eliza Hamilton a century earlier, another uptown resident stepped forward to further literacy in northern Manhattan—an unlikely savior neither wealthy nor well-known.

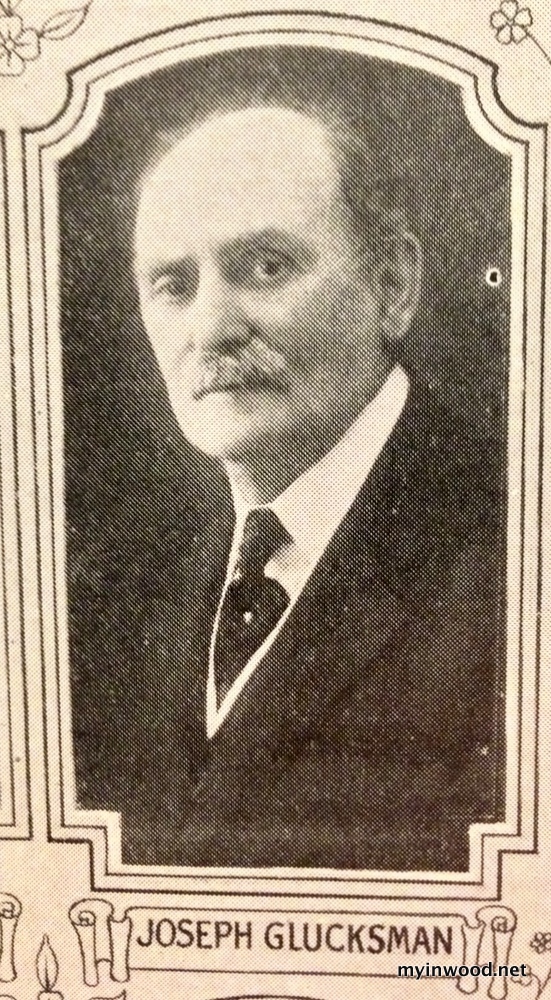

Joseph Glucksman, if anything, was strikingly ordinary.

Glucksman had emigrated from Austria in 1890 and lived in a rented apartment inside 17 Post Avenue, with his wife, Amelia, and three young sons, Ira, Leo and Sylvan.

Beginning in 1916 the fifty-year-old insurance broker, nearly bald and often described as being in poor health, began campaigning for a true public library for the neighborhood.

It would prove to be a five-year battle

“He organized a small working committee and directly began solicitation for books,” reported one publication. “Thousands of volumes were pledged by the people of Inwood at his appeal.” (Home News, April 24, 1921)

“He applied to the various civic organizations of the neighborhood for aid,” the account continued, “but none of them gave him any real support, he asserts beyond the appointment of ‘inactive committees.’ He was therefore, forced to work almost entirely alone. When the matter of finding a building came up, two Inwood public buildings were suggested as temporary quarters—the Dyckman House and the George Washington High School.”

George Washington High School, which then shared space with P.S. 52 on Academy Street and Broadway, was clearly the better fit.

A study hall in the the three-story brick schoolhouse was offered up for Glucksman’s endeavor.

Associate Schools Superintendent John Tildsley declared that he “believed the proposed plan would be of advantage not only to the children of Inwood in general, but to the pupils of George Washington High School especially.” (Home News, April 24, 1921)

In April of 1921 the Inwood Public Library officially opened. Glucksman had outfitted a study hall with shelves purchased with donated funds.

“The New York Public Library,” it was reported, “co-operated with him to the extent of sending him several hundred books and giving the librarian of his choice a course of instruction in modern library methods.” (Home News, April 24, 1921)

On the Road Again

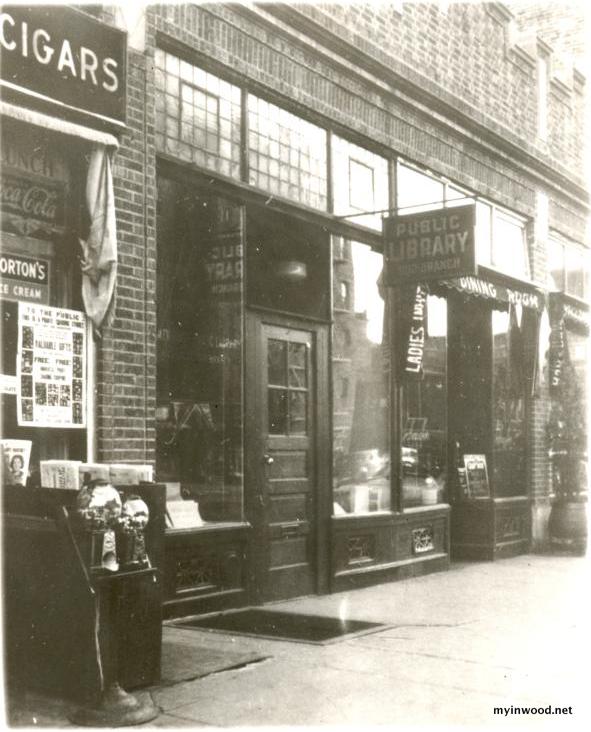

By 1925 the Inwood Collection—its history now intertwined with those of a General’s widow, a ship captain’s son, a Dutch landowner and an insurance salesman from Post Avenue—settled into a remodeled storefront on Sherman Avenue—today the site of a thrift store.

Remarkably, the Inwood Public Library remained on Sherman Avenue, sandwiched between soda shops, diners and taverns, for nearly a quarter century.

In 1952, more than ninety years after Eliza Hamilton’s generous gift, a “full-fledged neighborhood branch” of the New York Public Library opened on Broadway near Dyckman Street. (New York Post, July 23, 1952)

Postscript

In the 1924 the Dyckman Library, their goal having become a reality, became the Dyckman Institute. The fund, still alive today, provides need-based scholarships to students living in Washington Heights and Inwood.

As of this writing, a discussion brews regarding the future of the Inwood Library building located at 4790 Broadway.

A new library may be in the works. History will tell the tale.

Perhaps the new library will be named after Eliza. Just a thought.

[…] which still exists today as a family services agency named Graham Windham. In 1818, she opened the first school in the neighborhood of Washington Heights (where, decades later, Lin-Manuel Miranda would grow up). The Hamilton Free School was free of […]

[…] which still exists today as a family services agency named Graham Windham. In 1818, she opened the first school in the neighborhood of Washington Heights (where, decades later, Lin-Manuel Miranda would grow up). The Hamilton Free School was free of […]

[…] which still exists today as a family services agency named Graham Windham. In 1818, she opened the first school in the neighborhood of Washington Heights (where, decades later, Lin-Manuel Miranda would grow up). The Hamilton Free School was free of […]

In 1936 I started first grade in OLQM on Arden Street. Shortly after that we used to visit that little library. As I remember, there was a saloon nearby where my grandfather would sometimes enjoy a glass of beer, while I would have a soft drink served in a fancy glass. I never left without some pretzels tucked into a pocket… a dead giveaway that Grandpa had stopped for his “one beer”. I loved that place because it had a hitching post in front; memories of adventures in bygone days. Is it still there?