On July 20, 1916 Morton Freedgood celebrated his fourth birthday inside his parents rented apartment in northern Manhattan.

Woodrow Wilson was president.

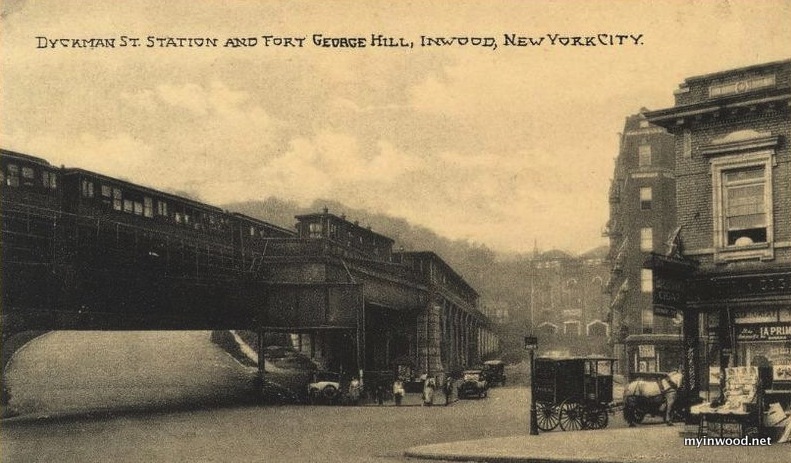

The subway had arrived to the region little more than a decade earlier.

“The scene,” he later recalled, was “our second-floor apartment in a six-story building on Nagle Avenue, in a northern outpost of Manhattan called Inwood, two hundred yards beyond the Dyckman Street station of the IRT, where the subway train, like some giant segmented worm, suddenly emerges half-blinded from its tunnel into the bright sparkle of daylight.”

The Freedgoods were the quintessential immigrant family.

Morton’s mother was Ukrainian—the oldest of nine brothers and sisters. His Russian father was a sharp dresser and liked to dance. Strangely, Morton never learned what his father did for a living.

The family was Jewish.

The Freedgood’s lived in Inwood through the early 1920’s.

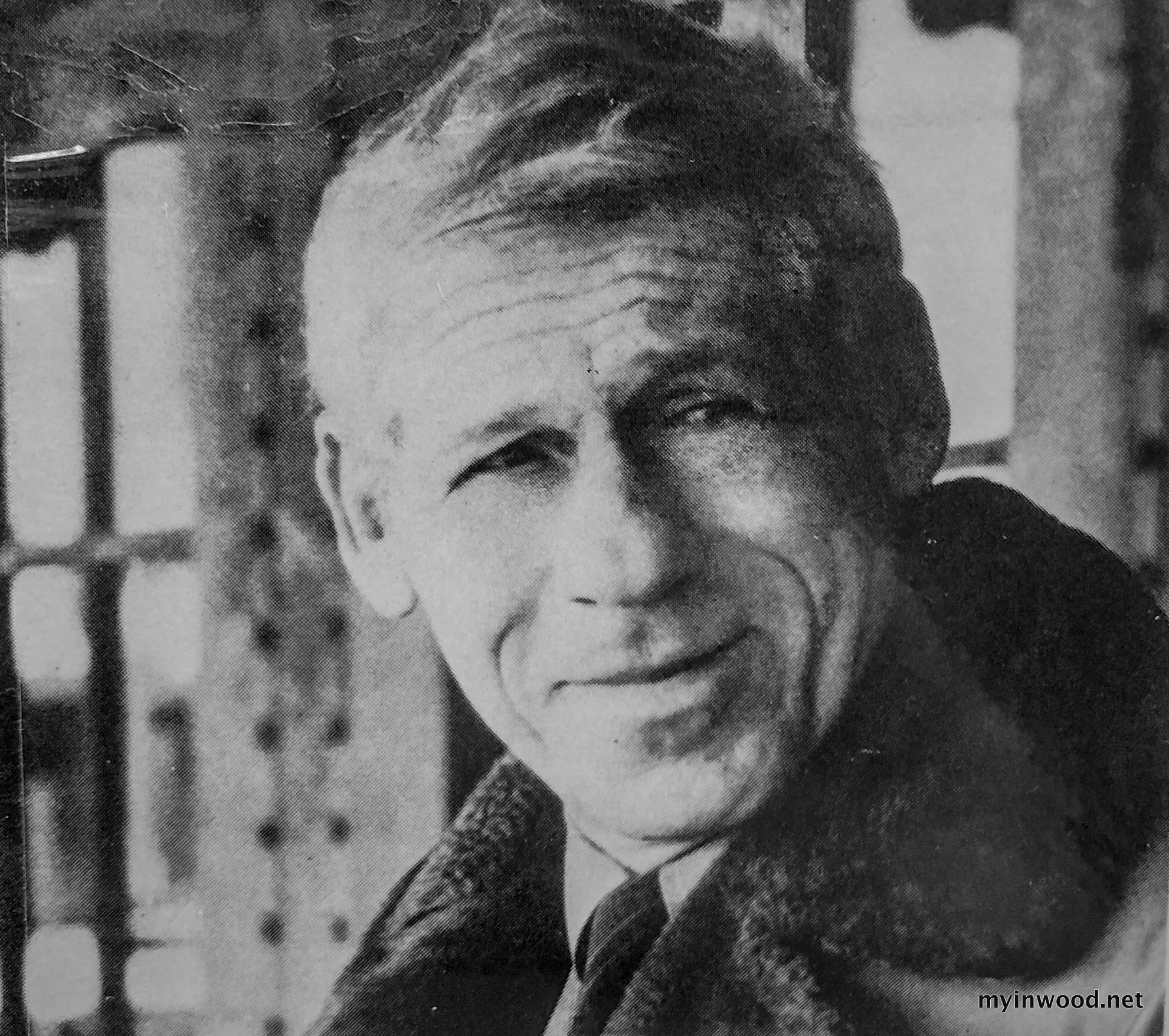

As an adult Morton Freedgood became an accomplished writer. His works appeared Collier’s, Esquire and Cosmopolitan.

In the late 1950’s Freedgood began writing crime novels under the pen name John Godey. He took the name from a nineteenth century women’s publication titled “Godey’s Lady’s Book.”

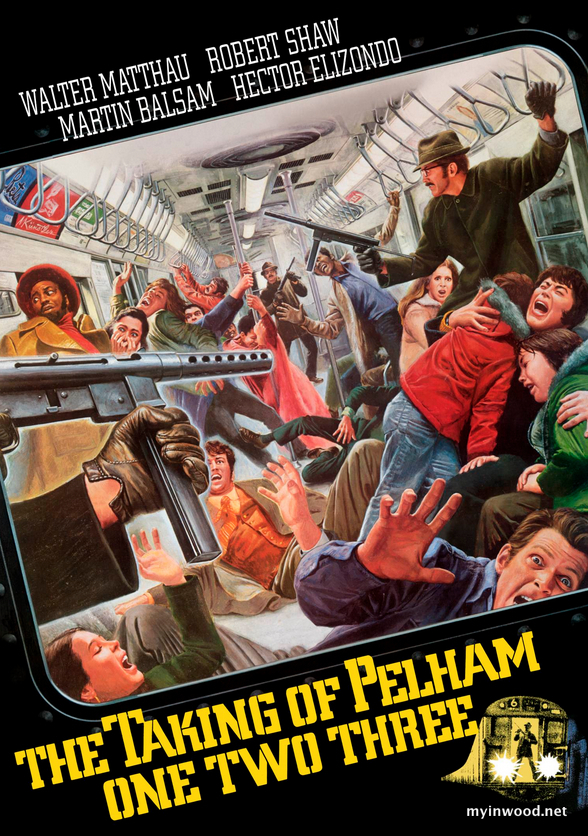

His 1973 book “The Taking of Pelham 1 2 3,” about the hijacking of a New York City subway train, written under his pen name, became a best seller. In 1974 the book was made into a movie starring Walter Matthau and Robert Shaw.

That same year Freedgood/Godey penned another book—a childhood memoir titled “The Crime of the Century & Other Misdemeanors.”

In the book Freedgood described the Inwood of the nineteen-teens from a child’s perspective.

“The Inwood of those days so abounded in glories that it might have been stocked,” Freedgood/Godey mused, “as trout streams are stocked, with features expressly designed for the enjoyment of kids.”

There was Fort George Hill, “so vertiginously steep that automobiles came from all over the state to test their climbing ability on its cobbled and curving ascent.”

The Spuyten Duyvil Creek, “whose treacherous eddies were a notorious drowning place for little boys.”

And the Dyckman Street Ferry “which, for five cents, would transport you” across the Hudson River to the Palisades.

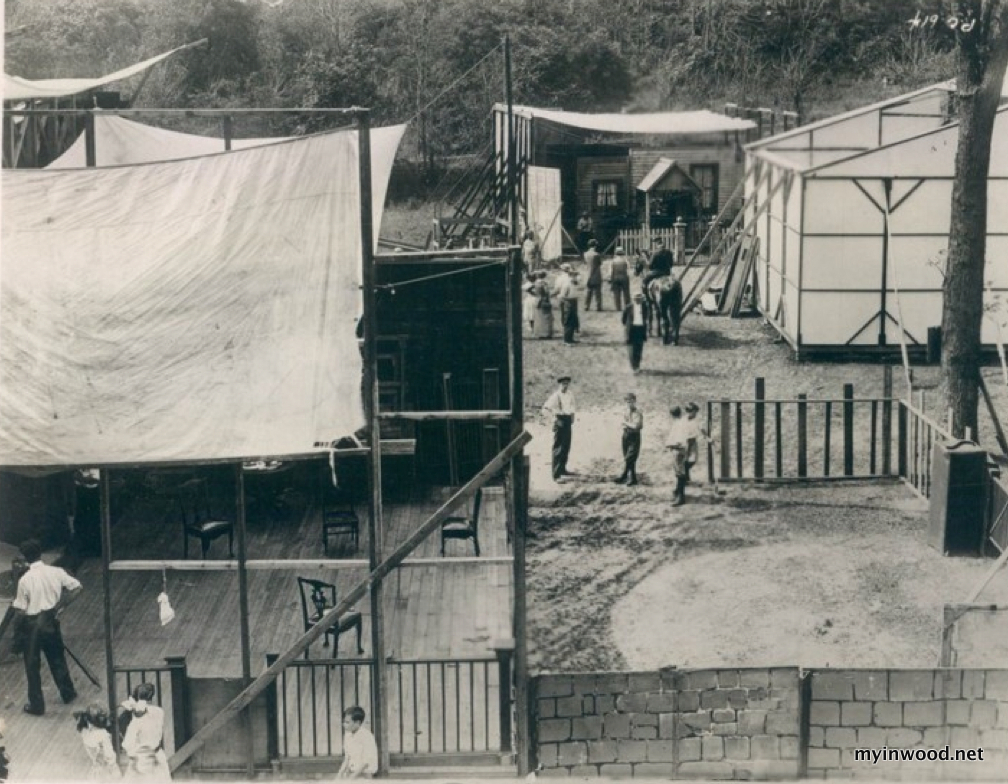

“Fort Lee lay on the other side of the river and sometimes the film companies would come over on the ferry from their studios and shoot two-reel comedies on Inwood Streets.”

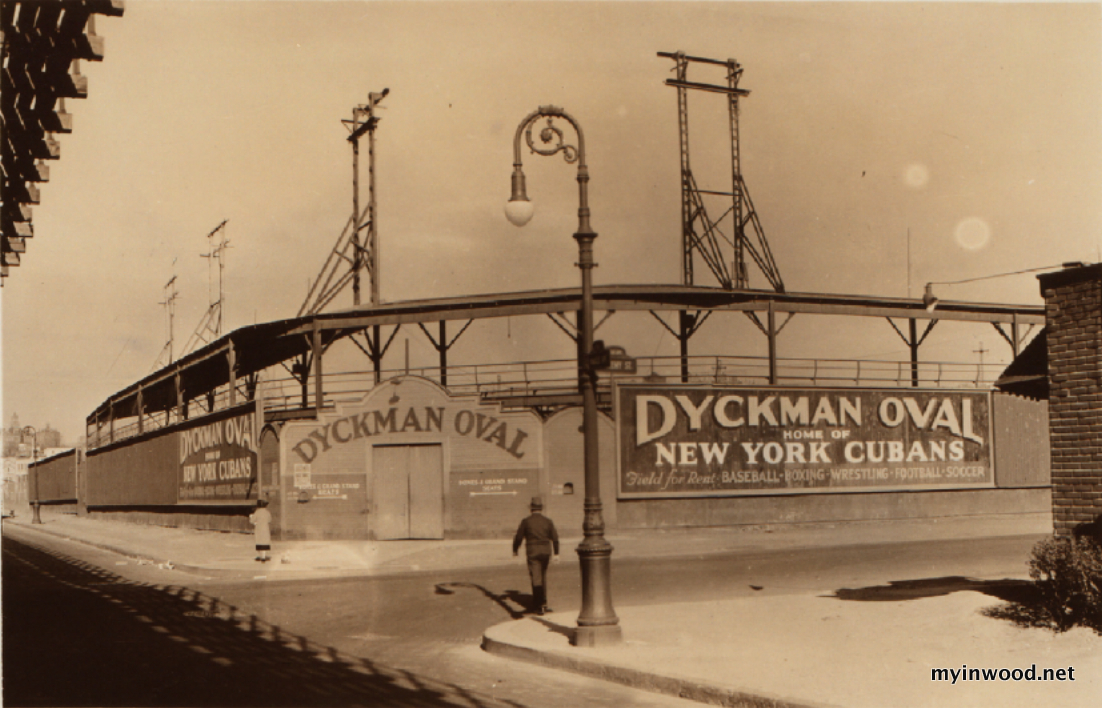

On summer evenings Freedgood often made his way to the “White Rocks,” a cliff-like rock outcropping near his apartment that overlooked the Dyckman Oval baseball park.

There, atop his rocky perch, he watched Jeff Tesreau’s Bears, “a semi pro outfit that played on weekends.” He also saw boxer Gene Tunney “in Kelly green trunks win a ten-round decision from Augie Ratner.”

“The ‘White Rocks’,” Freedgood wrote,” was a plateau, many blocks long, rising to a more of less uniform height of perhaps thirty or forty feet above street level. Atop it or, more accurately, in its fastness, it was a wilderness of brush, weeds, trees, rises and falls, caves and escarpments, marshy here and desert dry there. It was a lost world, a gift from a god acutely sensitive to the needs of little boys. You could wander its terrain for hours, absolutely insulated from the life of the city, from duties and repressions. It was my Treasure Island, my Far West, my Spanish Main, my Himalayas, and my Africa.”

“Places exist as much in time as they do in a spatial dimension,” Freedgood pondered.

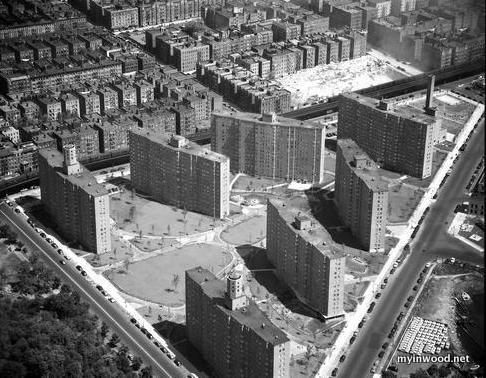

“Except that its coordinates are the same, there is little relationship between the Inwood of fifty years ago and the Inwood of today. This is neither guesswork nor sentimentality. I saw it recently. It’s a different place.”

Freedgood died in 2006 at the age of 93.

Click below to purchase a copy of Lost Inwood.

Does anyone remember Mante’s Bakery which was on Dykeman Street not far from the 10th Ave, train depot?

I left Inwood in 1951..