On December 21, 1937 Lionel S. Mapleson, the longtime librarian for the Metropolitan Opera, suffered a fatal heart attack inside his 10 Park Terrace East apartment in the Inwood section of Manhattan.

At the time of his death the 72-year-old Inwood resident was legendary for maintaining a vast collection of music that was sometimes loaned to orchestras throughout the world.

History however would remember him as the father of music piracy—an operatic bootlegger of the first order.

A Musical Heritage

Born in London in 1865 Mapleson came from a long line of music librarians dating back to the 18th Century. His father, Alfred Mapleson, was librarian for the Convent Garden Opera House. He was the nephew of the famous impresario “Colonel” James Henry Mapleson. His great-great grandfather was Benjamin Mapleson.

Before immigrating to New York in 1889 Mapleson’s father trained him to be a music librarian, though the younger Mapleson’s dream was to become a concert level musician. In New York he joined the chorus of the newly formed Metropolitan Opera, then in its sixth year, before assuming the position of Librarian. He would hold the position for 48 years.

“As a young man Mr. Mapleson played first violin in the orchestra of Hans Richter in Europe,” wrote the New York Times. “He came to the United States to play the viola in the Metropolitan orchestra in 1889, six years after the foundation of the company.” (New York Times, December 23, 1937)

Mapleson married Helen White, a soprano in the company, in 1893.

Musical Piracy

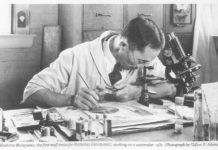

In 1900 Mapleson purchased a Model A Edison cylinder phonograph and was enthralled by the sounds it produced. A friend realized Mapleson’s excitement and soon presented a gift of a Bettini recorder and reproducer.

Now the librarian could record his own audio.

How often he must have dreamed of hearing his collection played in the music halls of ages past. Now he could record the great artists of his day for future generations.

On Thursday, March 22, 1900 Mapleson wrote in his diary, “For the present, I neither work properly nor eat nor sleep. I’m a phonograph maniac!! Always making or buying records. The Bettini apparatus is simply perfect.”

This suitcase-type device was highly portable and Mapleson delighted in making home recordings of his family and children at play. The wax cylinders could be shaved down and reused. This also meant the grooves were easily damaged.

Mapleson wasted no time in recording artists at the Met. The wax cylinders were capable of recording two minutes of audio. He sought permission from the Met before commencing his experiments.

In 1902 Mapleson began recording from a catwalk forty feet above the stage. Surviving recordings include French soprano Emma Calvé in Carmen and Faust and Albert Alvarez in Le Cid.

In 1903 Mapleson hit his stride, recording snippets of at least 17 operas. These later recordings included Nordica in Die Götterdämmerung, Lillian Nordica in Die Walküre and Fritzi Scheff performing in Faust.

That same year his first son, Louis A. Mapleson, was born.

In 1904, for reasons unknown, Mapleson abruptly ended his operatic recordings. In 1903 professional recording companies approached the Met about recording operas, wrote David Hall in The Mapleson Cylinders—A Historical Introduction. Perhaps they persuaded Mapleson to end his amateur recordings. Perhaps the artists themselves complained.

At Home in Northern Manhattan

The 1920 Federal census shows the fifty-one year old Mapleson living in a rented apartment in 5000 Broadway with his wife Helen and sons, Louis and Alfred.

By 1930 the family had moved to a fourth floor apartment in 10 Park Terrace East across the street from Isham Park.

His recording days behind him, Mapleson’s recordings might have been forgotten if not for a 1935 mention in the New Yorker Magazine’s “Talk of the Town.”

In 1937, months before his death, Mapleson met with William H. Seltsam, the secretary of the International Record Collectors’ Club. Mapleson loaned the collector two of his precious cylinders.

After his death Mapleson’s estate allowed Seltsam to examine some 120 remaining cylinders. In 1939 the collector began converting the recordings to 78-rpm discs.

Through the years other cylinders surfaced. Some were found in a Brooklyn junk shop while others hade made their way as far south as Mexico.

Postscript

Mapleson’s son, Alfred, assumed his father’s role as Met librarian in 1938.

Mapleson’s wife, Helen, died on December 12, 1961. She was 91.

More than 100 recordings, now known as the “Mapleson Cylinders,” survive today.

In 1985 the New York Public Library transferred the scratchy, century-old recordings to six LP’s for public consumption.

1903: Faust Waltz

Recorded live at the Met by Lionel Mapleson

Cole,

I can’t believe that I never knew that Lionel Mapleson was an Inwoodite! Having worked for the Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center in the late 90’s, I knew the people that were involved in the transfer of the Mapleson cylinders and I also know what I big deal it was that these recordings were made and that they survived (wax cylinders are not exactly durable). I do know that many musicians that played with the NY Philharmonic or at the Metropolitan Opera chose to live up here, in fact Eugene Ormandy’s brother, Martin, who played cello in the Philharmonic, was a resident of my building some years before I made it to the neighborhood, but I had not heard about Mapleson and Park Terrace. You learn something every day.

Keep digging stuff like this up.

Hi Cole,

It was Leo Stern who gave Lionel Mapleson the Bettini attachment. I wrote an article entitled “Bettini and the Mapleson Recordings,” which was published in the July-August issue of

CANADIAN ANTIQUE PHONOGRAPH NEWS. You can see that issue’s front cover, which has one of the famous photos of Lionel Mapleson posed with a phonograph, by going to the Canadian Antique Phonograph Society’s website, then clicking on the Index under Bettini, and finally using the link next to Mapleson. While I have that issue in its printed format, I have to admit that I’ve been having a technical problem accessing all of it online. But then again, my computer skills are not the best. In the near future, I can have the publication scanned and sent to you as an attachment. Thank you for the wonderful tribute you have given to Lionel Mapleson on this website. Bettinialy yours, robert