On Dyckman Street, around the corner from the mofongo house, just east of Broadway, sits an imposing brick apartment building that dates to the turn of the last century.

When 207-209 Dyckman Street, actually twin buildings named the Solano and Monida, opened in 1904, they were billed as “high class” apartments.”

“Everything in them is of the best,” the developers claimed, “with all that the word ‘best’ implies.” (NY Sun, November 4, 1904)

Perhaps it was just such an advertisement that attracted a flying hero of World War One, the real life “Canadian Lindbergh,” to the Dyckman district of northern Manhattan.

It was here, in a neighborhood called Inwood, that the celebrity aviator hung his hat not long after the Great War ended.

In the 1920’s J. Erroll Boyd was a pretty big deal—a war hero, daredevil pilot and writer of hit Broadway songs.

His wife was a dancer. Al Jolson, a personal friend, hosted a party for the couple when they were newlyweds.

Heads must have turned when the handsome couple hit the street.

It’s safe to say that J. Erroll Boyd remains, to this day, the most celebrated Canadian to have lived in the neighborhood—even if you’ve never heard of him.

Hero of Dunkirk

James Erroll Dunsford Boyd was flying at an altitude of 12,000 feet over German-occupied Zeebrugge, Belgium in October of 1915 when his Wright biplane was ripped apart by anti-aircraft fire.

Miraculously, despite damage to the engine, propeller and wings, Boyd managed a forced landing just inside the Dutch border.

The twenty-two-year-old pilot, on loan to Britain’s Royal Naval Service, had been stationed in Dunkirk, France. Typical assignments included perilous missions hunting Zeppelins and dropping primitive bombs on submarines.

He would become a prisoner of neutral Holland.

His wartime internment proved a civilized arrangement.

With a promise that he would not escape Boyd was allowed to live out the rest of World War I under parole in The Hague.

He was also allowed to visit his native Canada and the United States from time to time.

On such a visit, in 1917, Boyd married an old sweetheart, Evelyn Carbery.

Evelyn was a theatrical dancer. Jazz singer Al Jolson threw the newlyweds a party.

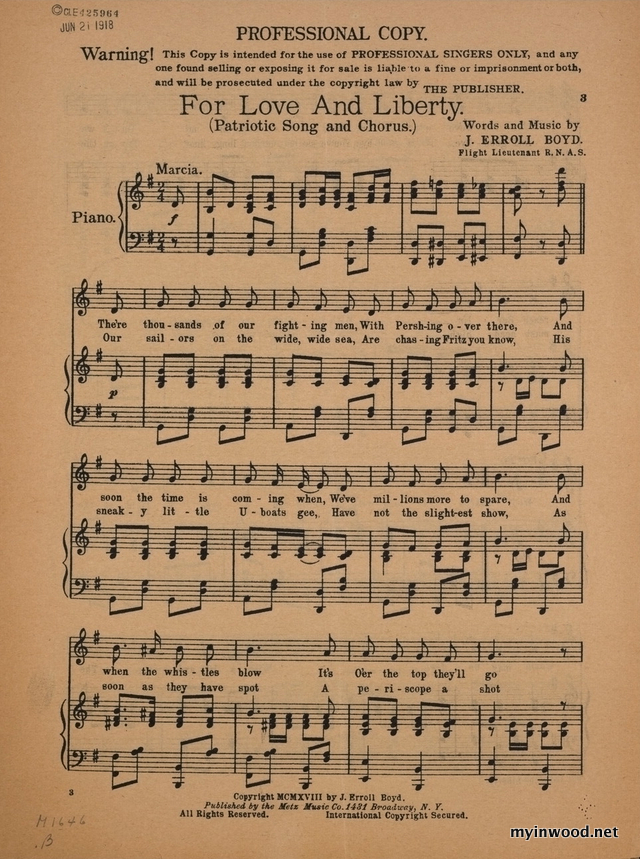

During the soiree Boyd, an aspiring songwriter and talented pianist, penned a song titled “For the Love of Liberty,” which later became a popular hit.

Boyd, known to friends as “Erroll,” briefly ran a garage and car rental business in Toronto after the War.

But the daredevil pilot had his eyes set on New York.

Bright Lights, Big City

In 1919 the Boyds moved to Manhattan to promote his music career.

One of his songs, titled “Dreams,” became a Broadway hit.

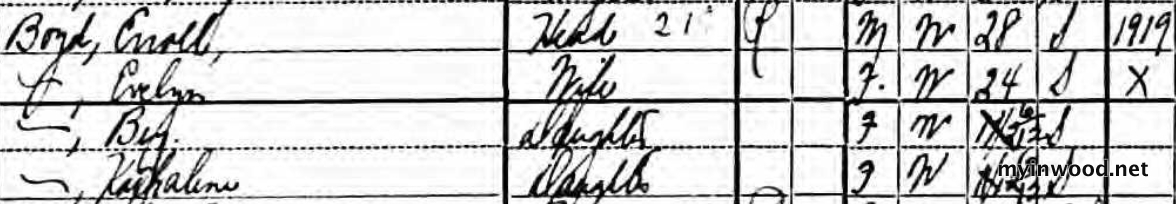

The family, which now included daughters, Bey and Kathleen, moved into a rented apartment in the Inwood section of northern Manhattan. Three more daughters, Jean, Honor and Virginia, would follow.

The apartment house was just blocks from the elevated subway station. Bakeries, shops and restaurants lined Dyckman Street. Much of the “newly discovered” region was still under construction.

Neighbors in 207 Dyckman Street, a six-story walk-up near Broadway, included a reporter, an engineer, two architects, a photographer, and a chemist—professionals for the most part. Tenants of the brick apartment house were a mix of native-born Americans and immigrants from Russia, Germany, Ireland, England, Hungary and elsewhere.

Boyd was undoubtedly a well known figure in the neighborhood.

When visited by a census taker in 1920 he listed his occupation as “aviator.”

The family remained in New York through the mid-1920s.

During this time Boyd honed his flying skills and even did some skywriting to promote his songs.

Then tragedy struck.

In 1924 the Boyd’s daughter daughter, Jean, fell out of an open window to her death.

Boyd stopped writing music and moved his family to Detroit.

Canadian Lindbergh

In 1930, inspired by the first transatlantic flight by Charles Lindbergh, Boyd became the first Canadian to fly solo across the Atlantic flying from Canada to England.

Three years later he made the first non-stop flight from New York to Haiti. Before departing the President of Haiti presented the Canadian with gifts to deliver to American President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Boyd became an American citizen in 1941.

He died in 1960.

In 2017 Boyd was inducted into Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame.

Click below to purchase a copy of Lost Inwood.