In the late 1800’s an eccentric publisher named Joseph Keppler built a splendid home atop Inwood Hill in the northernmost reaches of Manhattan.

Surrounded by wealthy neighbors also itching to get away to the “country” Keppler was able to keep his brood away from the rowdy chaos of downtown while maintaining a position of considerable power in the city below.

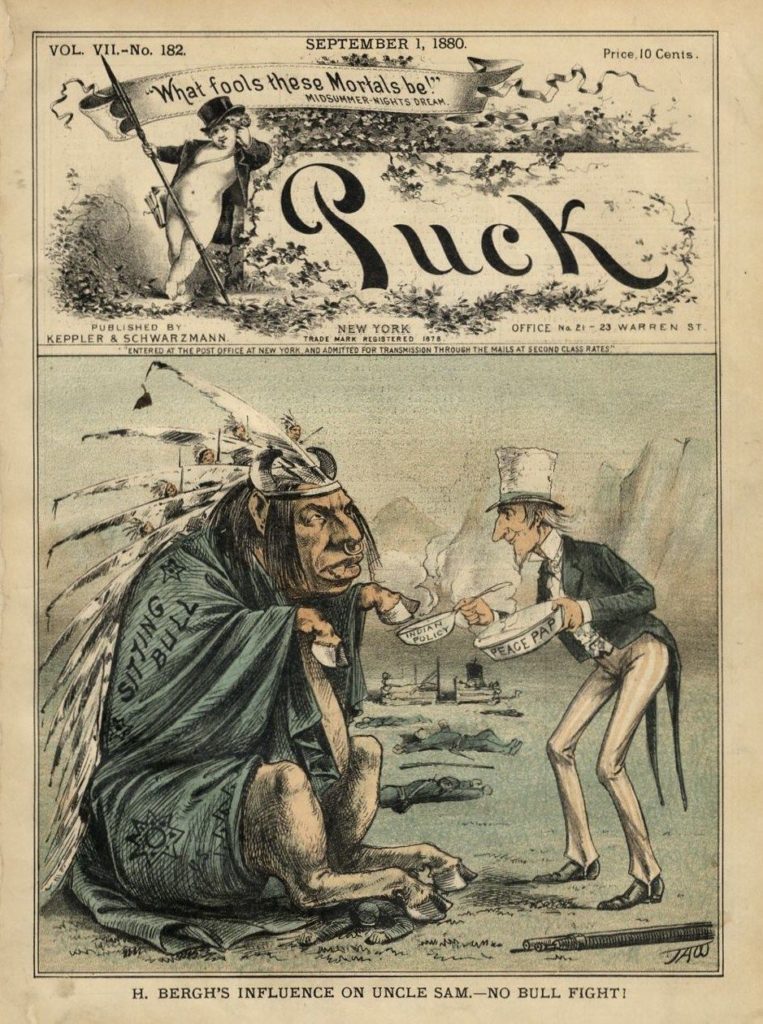

In his day everyone knew the name of the publishing titan and his often-controversial Puck magazine.

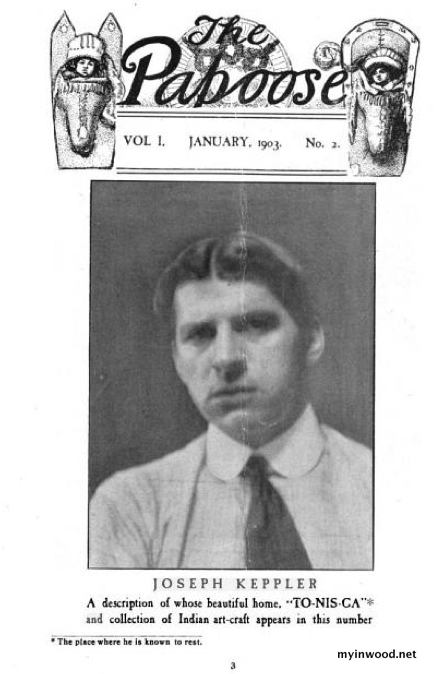

Joseph Keppler

Born in Vienna in 1838, the son of a baker, Keppler would become the founding father of satirical cartoons in the United States.

His father, whose fancy designs for wedding and birthday cakes thrilled wealthy clients, inspired Keppler’s early fascination with art. The young Keppler often recreated his father’s artistry in ink and sometimes found his works published in German comic papers—but the work barely paid his rent.

Around 1869 the young artist set sail for America looking for a broader audience and a chance at fame and fortune.

He landed first in St. Louis where, after several false starts, he founded “Puck,” an illustrated magazine of political and social satire.

But St. Louis was a poor town and the venture failed within months of its launch.

Discouraged Keppler moved his operation to New York City in 1872 where the publishing elite quickly took notice.

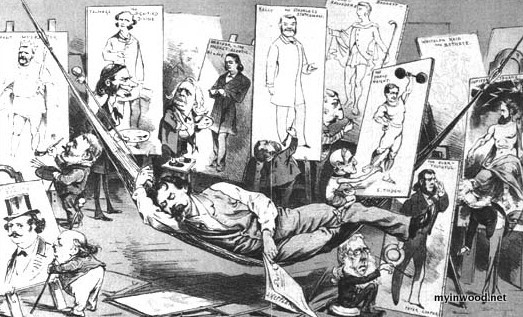

During those early years Keppler often teamed up with noted cartoonist Matt Morgan, working for various publications including Frank Leslie’s Illustrated.

In 1876, his confidence restored and his funds replenished, Keppler revived Puck, which became an instant sensation. Readers in America and those as far away as England devoured every copy. Soon Keppler was a very wealthy man and an inspiration to a generation of young cartoonists.

Keppler stood five-foot-ten and was said to comport himself with a military bearing replete with a signature goatee and mustache–a dashing and brilliant character.

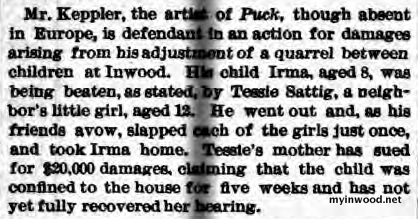

Keppler moved to Inwood sometime before 1880. There, overlooking the Hudson River, the publisher and his wife, Paulina, would raise three children, Irma, Olga and Udo.

Among the woods of northern Manhattan Keppler pondered upon the lives of the Lenape people—the Native Americans who called this region home centuries earlier. Arrowheads and oyster shells from long forgotten feasts were often found underfoot about the property.

On these walks in the wilderness, downtown but a dream, his young son, Udo, developed a passion for protecting and exploring Native culture.

From an early age Udo understood that his own backyard had once been the seasonal retreat of the Lenape. Fascinated, the young German-American began preserving, collecting and documenting Native American customs and artifacts.

Udo, like his father, was also a noted cartoonist—but his life’s ambition, to keep alive the memory of ancient peoples, never waivered.

Udo Keppler

In 1894 Joseph Keppler died of heart disease and left his estate to Udo.

Not long thereafter Udo legally changed his name to Joseph Keppler, Jr. to honor his father.

By the turn of the century Udo became active in Indian affairs as well as an avid collector.

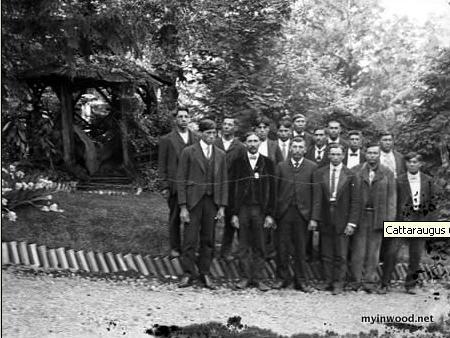

In 1899 Keppler was elected an honorary chief of the Seneca Indians and was given the name Gy-ant-wa-ka. Friends often referred to him with a variety of nicknames including “Kep” and “Chief.”

A 1904 newspaper article described a Thanksgiving Day “Indian Council” held in Keppler’ s Inwood home attended by “forty to fifty Indians from different parts of the country.” (The Sun, November 27, 1904)

“The council was held in the dining hall in the Keppler home,” the article continued. “Here solid oak beams afforded a sound footing for the ceremonial dances.”

Until his death in 1956, Udo was a tireless defender of Native concerns; negotiating discounted train tickets for members of New York tribes.

He also helped introduce the world to the sport of lacrosse; sometimes inviting Native players to his Inwood home—a home full of remarkable Native treasures.

The Keppler Collection

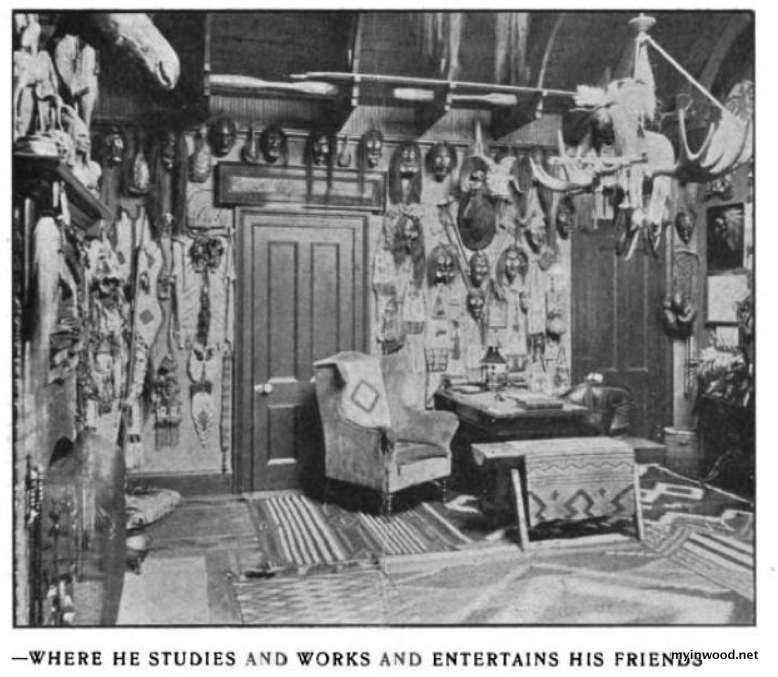

By the turn of the century reporters began to write about the unusual collection atop Inwood Hill.

“One of the most valuable private collections of Indian relics in the country is owned by Joseph Keppler of Puck,” one reporter wrote. “Mr. Keppler is a cartoonist, as his father before him. He became greatly interested in Indians a t the age when boys usually think that the highest ambition in life is to become an Indian scout, and, though his ambitions have changed, his interest in Indians has grown stronger. Mr. Keppler is an Indian chief by election. His house at Inwood is filled with Indian relics, among them being several very valuable wampum belts.” (Los Angeles Herald, November 9, 1901)

Two years later a writer for a publication titled the Papoose gave readers a better glimpse into Keppler’s inner sanctum. The visitor described a beautiful collection whose “wealth of color and originality of design” proved nearly impossible to describe or even photograph.

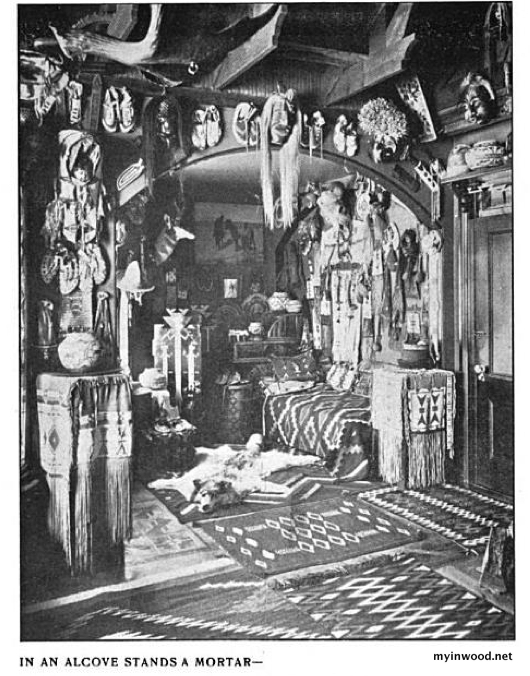

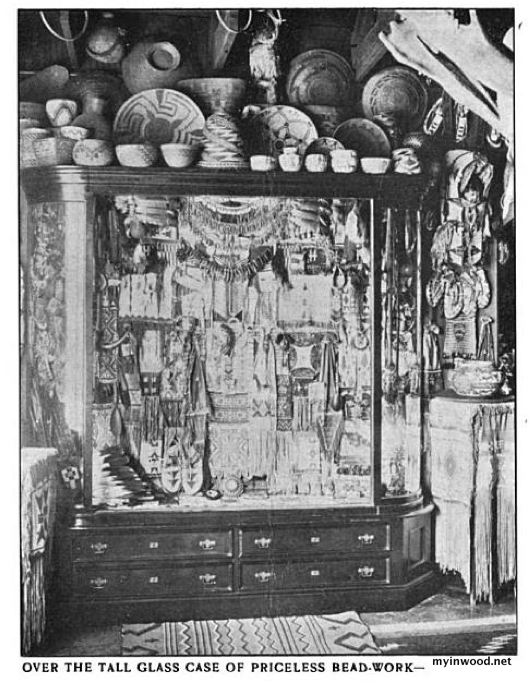

“The floors,” the account begins, “were carpeted with the marvelous work of the Navajo, rich with warm coloring, and walls thickly covered with articles of dress and ornament, implements of war and for the chase. Beautifully beaded moccasins, pipe bags, belts, papoose carriers, leggings, sheaths for the hunting knife and hundreds of smaller articles are artistically grouped for the best effect. In one corner a glass case contains some of the finest pieces of woven bead-work this it has been the writer’s privilege to examine. Here the best productions of the Winnebago, Chippewa and Algonquin bead-workers are grouped. Belts and sashes, in which wonderful designs are traced in harmonious coloring, hang side by side with rare designs in richly dyed quills of the porcupine. On the south wall hang over half a hundred masks used in Iroquois ceremonials and dances, all carved from solid wood and each of a different design and meaning.”

Postcript

In 1917 Puck was sold to William Randolph Hearst. Puck was shut down in 1918.

Inwood Hill became a park in 1926. All former residences were demolished by the late 1930’s.

Udo Keppler died in La Jolla, California in 1956. He was 84.

Today the Museum of the American Indian houses a significant portion of Keppler’s collection.